This week we’re returning to the States to meet poet, LindaAnn LoSchiavo, as she reflects on a poem from her collection, Apprenticed to the Night.

My latest poetry book has an unusual backstory: the pandemic and my telepathic parents.

My parents communicated telepathically — mostly when my father was at work. She was a stay-at-home Mom; he was a shipman in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and had no access to a telephone. When I was too young for school, she’d ask me to play quietly and then converse with him. Naturally, I thought all married couples could transmit thought messages.

I inherited this useful ability, which granted me access to communications “across the miles,” so to speak. For example, I could reach my father while he was driving and insist that he turn around and come home. I kept this channel open so the dead could reach out, too; My Dungeon Ghost is a memoir poem about an elementary school classmate who became a paid assassin, died behind bars, and telepathically requested “a boon.”

With outsiders, this was never discussed, even though my family considers telepathy to be a normal thing even children are expected to do. Though I’ve had my share of uncanny conversations and experiences, I deliberately excluded these from my writing. Then the pandemic arrived with a panicked lockdown — and the silken privacy of isolation granted permission to open a locked door. I decided this collection would be different: a conjuring of the literary and speculative, the familiar and the alien, with judicious sampling from other poets.

Apprenticed to the Night (2023) treats mortality, betrayal, memory, trauma, and the bewilderment of loss as constantly shifting enigmas. The formal verse shifts gears into haibun, sonnets, heroic couplets, nonets, and blank verse — innovating inside the lineage of memorable poets (Christina Rossetti, Sara Teasdale, Robert Frost, Muriel Rukeyser, James Merrill, Jorie Graham, etc.), whose poems are repurposed (in Golden Shovels and Centos) as frames and mirrors for the text, stitching past and present in a complex, vibrant dialogue.

Curiously, even as I was keeping my real life off the page, I noticed confessional poetry was gaining popularity. There’s a human desire to be seen as if to give importance to one’s life. Therefore, in Apprenticed to the Night, I decided to switch between my stories and other people’s truths by writing poems about their losses, too, their beloved sisters dead from cancer or homicide; fathers my friends had lost to alcoholism, abandonment, or infidelity; lovers they had lost on the battlefield or to COVID — as a way of being connected to the collective past not by recall nor first-hand experience but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation.

Some book reviewers have mistaken various poems in my collection as autobiographical when these might have been based on borrowed traumas. I’ve always had the desire to shrug off my tight-fitting New York-ishness to slip into another skin and then another, giving voice to a bottomless pool of female grievances. In the same way that actors shed an identity to step into a role, the absence of me on the page provided a more direct pathway into someone else’s agitation — and a way to avoid my own.

Though authors are often on a journey toward an understanding of the self, their roots, and the past, writing about my difficult parents has always been a struggle. I had to find a strategy.

By choosing to frame my relationship with my mother during the interval of her late-stage cancer when I was her sole caretaker (in my parents’ home in the Sun Belt), the potency of her past abuse could be diluted. Moreover, since my ghostly guardians followed me to Florida, I had an inkling there would be supernatural surprises in store. And there were. [Sorry, no spoilers. Read about it in the book.]

Her funeral was held in the living room. Then the morgue promptly removed her body.

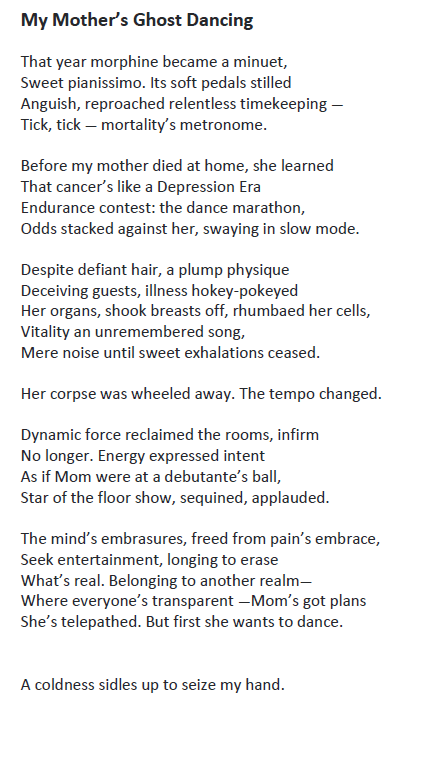

After being bed-ridden for months, my mother’s ghost cheerfully reclaimed her home. It was thrilling to feel her spirit moving energetically from room to room, delighted to be free of illness, and telepathing her joy to me. This supernatural experience informed My Mother’s Ghost Dancing.

This poem came in as a contest finalist and has also been the focus of a few readings I’ve done. Having created such a stir, subsequently it inspired me to write similar poems during this spring.

Eventually, these 24 poems became their own chapbook Cancer Courts My Mother. I sent five of these poems and a proposal to a university press in California. It was quickly accepted for publication.

Forthcoming in 2024: Cancer Courts My Mother (Penumbra / Stanislaus State College).

Read my review of Apprenticed to the Night by LindaAnn LoSchiavo next week.

One thought on “Drop-in by LindaAnn LoSchiavo”